Phoebe Palmer

Phoebe Palmer (1807-1874)

You can hear an audio recording of this post on Episode 53 of the Methodical Methodist Podcast!

She was one of the most influential voices in 19th-century Methodism—so influential, in fact, that many have called her the “mother of the holiness movement.” Phoebe Palmer was a wife and mother, a writer and speaker, and a devoted follower of Christ. Through her Tuesday Meeting for the Promotion of Holiness in New York City, she inspired countless pastors, missionaries, and laypeople to pursue a deeper life of faith. Her books and sermons spread far beyond her own community, shaping Methodist theology and fueling revival across the United States and even in Britain.

Phoebe Palmer believed that holiness was not a distant goal reserved for a select few but a gift of grace available to every believer. Her passion for evangelism and her tireless advocacy for women in ministry challenged the church to expand its vision of who could proclaim the gospel.

Phoebe Palmer was born as Phoebe Worrall on December 18, 1807, in New York City to her parents Henry Worrall and Dorothea Wade Worrall. Phoebe was their fourth child. Her father, Henry, was born in Yorkshire, England. When he was fourteen years old, he went to one of John Wesley’s 5:00 morning meetings at Bradford. This had a tremendous impact on his life, and he joined the Methodist society under the preaching of John Wesley. At the age of 25, he made the decision to immigrate to the United States. He married Dorethea Wade who was born in America. The two shared the same interest in the Methodist Church.

From a young age, Phoebe was immersed in the world of Methodism. She grew up in a home where Scripture, hymns, and theological discussion were part of daily life. In fact, they held family worship times twice a day at home, and they shared in family prayers at mealtimes. Her parents and mentors were deeply rooted in the Methodist movement. They taught her not just the stories of the Bible, but the history and heart of their faith.

At the age of eleven she scribbled in her Bible these words:

“This revelation—holy, just, and true—

Though oft I read, it seems forever new;

While light from heaven upon its pages rest,

I feel its power, and with it I am blessed.”

There’s a story of when she was 13 and she received a vision of Jesus coming to embrace her in his harms and tells her to “be of good cheer.” She had a strong sense of faith in these young and formative years.

Even as a child, Phoebe had a sharp mind and a curious spirit. One of her sisters once joked, “Phoebe knows nothing—she only thinks.” It wasn’t an insult, but an affectionate observation. Phoebe was the kind of person who couldn’t stop asking questions, who wrestled with ideas long after everyone else had moved on. She wasn’t content to simply accept what she was told—she wanted to understand it, to think it through, to make it her own. At an early age, she dedicated her life to Christ and become an active member of the Methodist church.

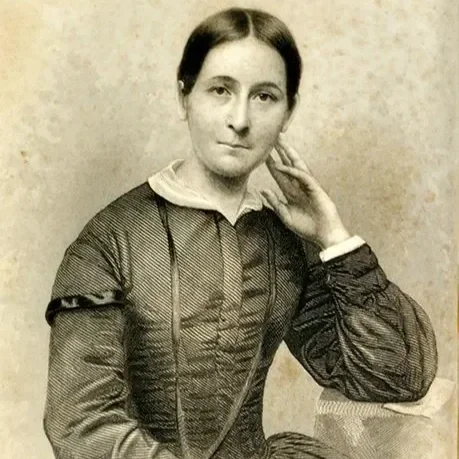

Young Phoebe Palmer

Phoebe was an avid reader. She read the Bible daily, but she also read biographies of famous Methodists like John Wesley and Susannah Wesley as well as other Methodist women leaders like Mary Bosanquet Fletcher, Hester Ann Rogers, and Nancy Cutler.

In 1827, at just 20 years old, Phoebe married Walter Palmer, a physician and fellow Methodist. In her journal she writes about their relationship right before their wedding saying, “The most eventful period of my life is approaching. During the past eleven months, friendship has been ripening into a mature affection between myself and a kindred spirit, who, I have reason to believe, is in every respect, worthy of my love.”

They were a very loving couple, unified and devoted to each other. Later during a time of illness Phoebe stated to her husband: “You have been one of the kindest of husbands to me; I could not have done what I have without you. Our love has been abiding, and it will abide forever. It will ever be one with Jesus.”

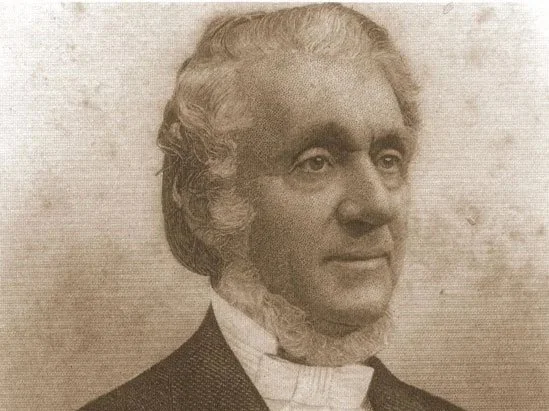

Dr. Walter Palmer

The couple had six children, but heartbreak came early—two of their sons died in infancy. And then, after ten years of marriage, on July 29, 1836, Phoebe rocked her 11-month-old daughter Eliza to sleep and placed her in her crib before going to her own bedroom. Soon after, Phoebe heard screaming from the nursery and came running. A nursery worker had tried to refill an oil lamp without putting it out. When the flames shot up, she had thrown the lamp away from her. It had landed in the crib. And tragically, Eliza passed away as a result of this accident.

Phoebe was stricken with grief, cried out in anguish, and paced the floor. She later wrote in her journal: “Never before have I felt such a deadness to the world, and my affections so fixed on things above. God takes our treasures to heaven, that our hearts may be there also. And now I have resolved that the time I would have devoted to her [Eliza] shall be spent in work for Jesus.”

Those losses would deeply shape Phoebe’s spiritual journey. Grief drove her to seek a faith that was not just intellectual, but deeply transformational. A year after this tragic experience, Phoebe experienced a sense of entire sanctification in her life. On July 27, 1837 she wrote, “Last evening, between the hours of eight and nine, my heart was emptied of self, and cleansed of all idols, from all filthiness of the flesh and spirit, and I realized that I dwelt in God, and felt that he had become the portion of my soul, my All in All.”

The Palmers were active members of Allen Street Methodist Church, one of New York City’s most prominent congregations. A revival there in 1831 rekindled their passion for God, and their growing interest in John Wesley’s writings led them to seek a deeper experience of holiness.

In her journal, she writes about this time of revival saying, “A remarkable revival is now going on in the Allen Street Church. It began with a four days’ meeting. The beloved pastor, Rev. Samuel Merwin, as he announced on the Sabbath that a four days’ meeting would commence… said that he hope it might be a forty-days’ meeting, and such it has proved to be… Hundreds have been saved through this great visitation of the Spirit, and still the work goes on in unabated power.”

This revival progressed over two years and brought many people to the faith. Many of those who responded to this outpouring went on to serve as ministers and answer calls to ministry.

In 1835, Phoebe Palmer started attending a small prayer gathering that her sister, Sarah Lankford, hosted every Tuesday in the Palmer’s home. These women would pray and study Scripture together. They called it The Tuesday Meeting for the Promotion of Holiness.

Two years later, Phoebe began to lead these gatherings herself. Her passion for holiness and her gift for teaching drew more and more people in. In fact, her home had to be enlarged to accommodate all the people who attended these meetings. What started in a single living room soon spread far beyond it, and the Tuesday Meeting became a model for more than two hundred similar gatherings around the world.

In 1840, she broke new ground as the first female Methodist class leader in New York. Phoebe opened the Tuesday Meeting to men as well. Some of the men who attended these meetings were Methodist bishops, theologians, and ministers including Edmund S. James, Leonidas Lent Hamline, Jesse T. Peck, and Matthew Simpson.

Phoebe taught on the doctrine of entire sanctification— or “Christian Perfection.” She believed that through God’s grace, a believer’s heart could be made perfect in Christian love.

Palmer wrote several books about the doctrine of Christian Perfection including, The Way of Holiness and The Guide to Holiness. Interestingly enough, The Way of Holiness was first published anonymously in 1843, but this book eventually went on to sell over 50,000 copies.

Phoebe’s ministry didn’t stop at the Tuesday Meeting. Around this time, Phoebe and her husband, Walter, started serving as itinerant preachers. They received more and more invitations from churches, conferences, and camp meetings. Walter would often speak at these meetings, but Phoebe was the one who was better known.

The couple began to lead numerous revival meetings and camp gatherings all across the United States and beyond. They would eventually minister over 300 separate revival meetings in the United States, Canada, and Great Britain. The Palmers meetings were so popular that special trains had to be scheduled to accommodate the large crowds.

One time while she was traveling on one of her evangelistic journeys, she is out on the ocean riding a steamer, and the boiler catches fire. The ship catches on fire, and everyone is panicking. And Phoebe calms the crowd down by leading them in singing hymns. And, apparently, when the ship finally pulled into the dock, one of the passengers called out, “Thank God for the Methodists.”

While preaching in the British Isles, they found themselves in the company of D.L. Moody and Charles Finney. While there, Phoebe resolved to reform British Christianity. She was really quite strict in some ways. In fact, she wrote to Queen Victoria, not once but twice, asking that the sovereign’s band not perform on Sunday. She also once refused to hold meetings in a church that allowed alcohol to be stored in the cellar. Still, because of her preaching skills, more than 20,000 of those who attended these meetings experienced salvation or a sense of sanctification.

Palmer was also very interested in community ministries. She was involved in one of the earliest prison ministries in the United States. She was a prominent member of the “New York Female Assistance Society for the Relief and Religious Instruction of the Sick Poor.” She was active in the establishment of the “Five Points Mission” which was a home for impoverished women and children, the first of its kind in America. She worked with the Methodist Ladies’ Home Missionary Society. She was a staunch advocate for abolitionism, temperance, and women’s rights.

She cared for children and took food, clothes, and medicine to needy families. Again, her husband, Walter was a doctor, and he would often provide medical assistance free of charge to patients in need.

She later gave her New York City home to the Salvation Army to be a home for single moms. This building later became the Salvation Army’s first general hospital in the United States. Overall, because of this missional efforts, Phoebe Palmer is acknowledged as one of the founding mothers of world missions in the American Methodist tradition.

As a female preacher, she faced plenty of criticism and pushback. As a result, she wrote her book The Promise of the Father which defended women in public ministry and made a theological case for women in ministry. She argued that the baptism of the Holy Spirit given at Pentecost was available to men as well as women. And she that that the Holy Spirit calls both men and women to speak out for Jesus. In Palmer’s sermon “Tongues of Fire on the Daughters of the Lord” she says this:

“God has given the word; and in this wonderful season of the outpouring of the Spirit, great might be the company who would publish it. This, in a most emphatic sense, is the day of which the prophet spake – when God would pour out his Spirit on his sons and daughters. Though many men have in these last days received the baptism of fire, still greater, as in all revivals, has been the number of females. These constitute a great company, who would fain, as witness for Christ, publish the glad tidings of their own heart-experiences of his saving power, at least in the social assembly.”

She realized that God had gifted her with the ability to preach, teach, lead, and write. And she stood firm in her calling. she refused to let cultural expectations silence that calling. Her courage opened doors for future generations of women in the church.

In 1864, the Palmers purchased a monthly magazine entitled The Guide to Holiness. It had first been started by Timothy Merritt to promote the doctrine of Christian Perfection. Phoebe edited this magazine for 11 years until the time of her death. It became one of the most popular religious magazines of the day and had subscribers in Canada, England, Liberia, India, and Australia. One commentator has noted, “Where Palmer could not go in person, she went through her books and magazine. She wrote 18 books of practical theology, biography, and poetry.”

Through her speaking and writing, the influenced people like Francis Willard, Catherine Booth (the cofounder of the Salvation Army); and John S. Inskip (the first president of the National Camp Meeting Association for the Promotion of Holiness).

Her impact didn’t stop with her own generation. Phoebe and Walter’s daughter, Phoebe Palmer Knapp, went on to compose over 500 hymn tunes that continue to echo through churches today including the melody for Fanny Crosby’s beloved hymn “Blessed Assurance.” It’s a fitting picture of legacy: a mother devoted to holiness and a daughter whose music still helps people worship the God her mother so faithfully served.

Phoebe Knapp Palmer

Palmer died of Bright’s disease in 1874 at the age of 66, but her legacy continues on. By the time she passed, those Tuesday Meetings had grown into something far bigger than anyone could have imagined—an international movement with more than 200 gatherings around the world. The holiness message she taught didn’t just stir hearts; it reshaped the American theological landscape and helped give rise to the Wesleyan, Holiness, and Pentecostal traditions. During her life Palmer spoke to over 100,000 people about Jesus and sparked a revival that brought nearly a million people into the church.

Her unshakable belief in the transforming power of God’s grace drew all kinds of people to her—the rich and influential, as well as the poor and forgotten. Thousands came to hear her preach the Word, and countless others were changed by her writings on what it means to live a fully consecrated life. Her ministry took her from New York to California, north into Canada, and across the Atlantic to the British Isles. And through it all, this ordinary woman—who sought nothing more than to be “fully conformed to the will of God”—became one of the most significant theological voices of the nineteenth century.

Bibliography

Philip J. Brooks, “Unsung Heroes of Methodism: Phoebe Palmer,” The United Methodist Church.

Sally Bruyneel, “Phoebe Palmer: Mother of the Holiness Movement,” CBE International, June 15, 2022.

John G. McEllhenney, “A Woman Who Proclaimed A ‘Shorter Way’ To Holiness 1807-1874,” General Commission on Archives & History.

Richard Wheatley, The Life and Letters of Mrs. Phoebe Palmer (New York, NY: W. C. Palmer, Jr., 1876).